Humans’ depictions of the wolf range from noble to fearsome. Which of the images on this page most resonate with you?

Image from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

Image by Charles Livingston Bull, courtesy of the Library of Congress

To understand attitudes toward the reintroduction of the wolf in Idaho, we need to first get a sense of how the wolf functions in the folklore of Idaho’s residents.

In recent years, photos of “giant wolves” shot “in Idaho” (and alternatively listed as Alberta, Manitoba, and Wyoming) have been circulated via e-mail, on Facebook, and elsewhere online.

Image source. (See other such images of hunters with dead wolves.)

In some instances, the text accompanying the photos states,

It is amazing how big they are. Deer, elk, and livestock killing machines. The big question you have to ask yourself is why? These massive wolves are not the native wolf that lived in our area 100 years ago. There was a reason these things where [sic] exterminated nationwide. They sure do look cuddly and cute. I wonder if our city dwelling tree hugger society that never has left a city really understands the impact of these killing machines.

The speed with which these photos went viral, especially on websites catering to hunters or ranchers, suggests many Idahoans share these beliefs—and these photos are designed to recruit additional believers. However, the wolves in the photos, while they might appear to be 200 to 225 pounds, weigh only about 80 to 100 pounds. The photos have not been manipulated in Photoshop or with similar software; rather, the camera lens and angle make the wolf appear much larger than it actually is. The Idaho Department of Fish and Game has confirmed this photo is a hoax and the largest wolf ever captured in Idaho was 135 pounds. The photos make clear that many people see the wolf as a literally larger-than-life figure.

A more realistic portrayal of a wolf hunt comes from Randy Newberg, who chronicled his trek with Matt Clyde through the rough terrain of Montana backcountry in the article “Like Elk, But Tougher.” Newberg’s 11-day quest to “fill” his wolf tag began with ideas about the wolf as his competitor for elk, admitting he had “complained long and loud of what unmanaged wolf numbers were doing to our elk herds.” When he and Clyde finally kill a wolf, however, he sees it instead as “an animal that needs elk as much as I need elk. An animal that by no choice of his own was caught in a crossfire of competing political interests.” He describes the black wolf in detail, declaring it “beautiful,” then continues,

It did not seem like the evil, fairy tale figure responsible for the demise of western civilization, which one might conclude by listening to the barstool stories of wolf-haters. In a lot of ways, its life seemed not too different from mine. It was born a hunter. It spent its entire life learning prey and their habitats. It needs wild places, free of roads and development. So do I. It eats elk. So do I.

My respect had grown. My attitude had changed. Chasing wolves in these mountains can do that, even to the most serious elk hunter.

As a vocal critic of how the wolf delisting process occurred, I found myself examining my earlier ideas of what was fact and what was fiction.

Newberg is not alone in trying to sort reality from fairy tale.

The wolf has appeared regularly in twentieth and twenty-first century pop culture. Movies like The Grey (2012) feature plane crash survivors who are picked off one-by-one by a pack of wolves. In the popular HBO series Game of Thrones, based on a series of novels by George R. R. Martin, the Stark family’s crest bears the Pleistocene-epoch dire wolf, and each of the Stark children adopts a dire wolf pup who, as it grows, becomes a familiar who protects them. Earlier, Farley Mowat’s 1963 book and 1983 movie Never Cry Wolf share the partially fictionalized tale of a wildlife biologist who finds that wolves’ impact on caribou herds isn’t as large as previously believed; in Mowat’s telling, the wolves survive part of the year on small game, including mice.

The wolf in European folklore

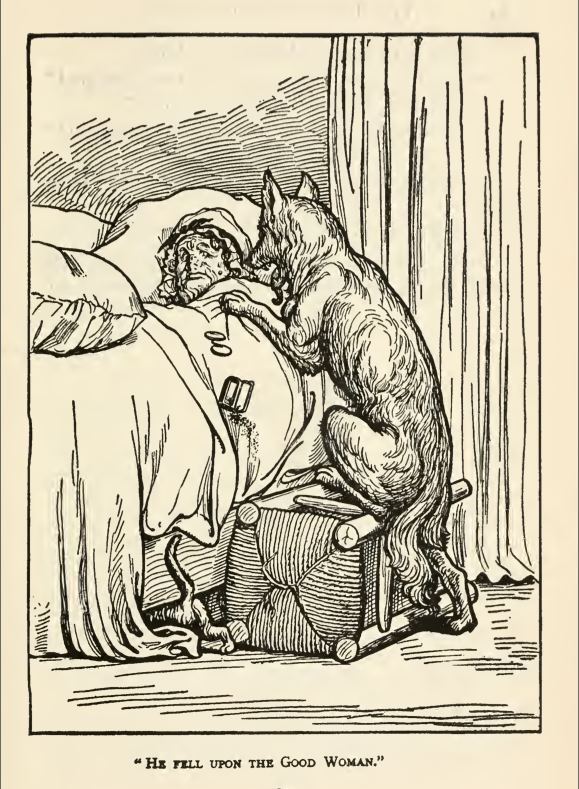

These popular culture manifestations of the wolf draw on older mythologies. For many Americans, our first introduction to the wolf is through folk tales and children’s stories, and the wolves that appear in them are rarely trustworthy. In some versions of “Little Red Riding Hood,” for example, the wolf eats the grandmother and the girl—and they are never rescued by a huntsman who slices open the wolf. Regardless of whether Little Red is resurrected from the wolf’s belly, in all versions of the tale the wolf is a manipulative, cunning, predatory creature who takes advantage of a naïve, innocent child. In various interpretations of the story, the wolf becomes a metaphor for night, winter, France, the chaos of nature, Little Red’s rite of passage into pubescence or womanhood, seduction, or rape.

Image by William Holbrook Beard, courtesy of the Library of Congress

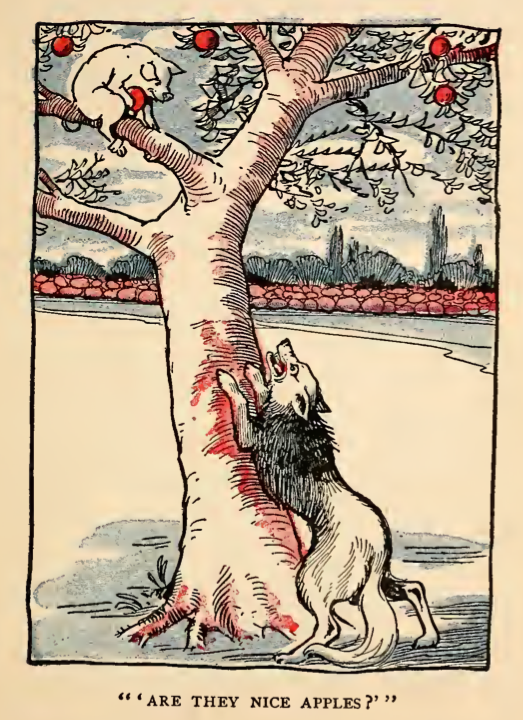

Similarly, in “The Three Little Pigs,” the wolf is malevolent and persistent, but we learn he can be outsmarted by the third, most thoughtful and careful pig.

Image by L. Leslie Brooke, courtesy of Archive.org

Image by John Rea Neill, courtesy of the University of Florida and Archive.org

The wolf in Native American folklore

While European folktales depict the wolf as untrustworthy or as an antagonist, the wolf that appears in western Native American folklore is a more ambiguous figure. In Pueblo Tewa mythology, the wolf and other predators greet humans as they emerge from the earth. The predators knock down and scratch the first man to make this trip, but he heals quickly and the wolf and the other animals assure him he is among friends. The animals outfit the man with hunting gear and provide him with the knowledge he needs to survive. As James Burbank explains,

The knowledge that Wolf and other predators give to the Tewa hero is not knowledge of good and evil as in the Biblical story of Adam and Eve, but knowledge of life and death and the interdependence of animal and human life cycles. It is an ecological knowledge.

The importance of, and attitude toward, the wolf has shifted in some indigenous cultures in the American West. In Navajo folklore, the wolf began its existence as an anthropomorphic figure, but increasingly it appeared in only its animal form and with diminished powers. That does not mean, however, that the wolf lost the respect of the Navajo people; Steve Pavlik explains that in Navajo belief, the wolf’s “powers are still considerable. Consequently, wolves are thought (along with bears and coyotes) to be among the so-called dangerous animals in terms of the sickness they can bring to people who have offended them in some way.” Pavlik hypothesizes that some of the wolf’s fall from grace can be attributed to Navajo contact with European Christianity, which tends to associate wolves with evil. In other tales, it’s clear Wolf is a leader, even among chiefs; in still others, he is responsible for rescuing a people in peril or even for resurrecting people from death. The wolf is so central to Navajo ideas about survival that the word naatl’eetsoh refers to not only wolves, but all hunters and predators, including human ones.

As told by Teresa Pijoan, one Zuni legend, White Wolf Woman, features a wolf who appears on several occasions to assist a woman traveling home after being kidnapped by the Navajo. The wolf provides her with warmth, food, and protection as he helps her navigate to her village. When she returns to her home to find her father’s dead body, she performs the funeral rites and then transforms into a white wolf. The story holds that this wolf woman guides lost travelers to their homes.

In this video, Horace Axtell, a Nez Perce elder, World War II veteran, and a leader in the traditional Seven Drum religion, explains the close historical connection between the Nimiipuu (Nez Perce) and the wolf.

The background noise in the video makes it difficult to hear Axtell’s story. Here are some of his remarks:

My grandmother used to talk to me about the wolf, and told me how important they were to our people when they lived out in the villages. . .They’d be sitting around the campfire at night, and all of a sudden they’d hear a wolf howl. . . And so they’d listen, and then the band would pretty much [remember] direction where the wolf sound was coming from, and they’d go over there in the morning, early. There’s a buck deer standing there, waiting for him. That’s the way it worked. That was a true story that Grandmother told me. That happened quite a few times.

That’s how important the wolf was to us, and never that I heard of anytime that our people had killed a wolf for the hide or anything–never did. Never did do that. It was always a close connection with the wolf and our people, the tribe, that way.

There are other things the wolf would do, also, to warn the tribe, warn the people if something else was going to try to come down, like a cougar, maybe. If that was going to happen, they’d come real close and do their howling to let, the warning. They were pretty closely connected to the wolf, and never did butcher a wolf for the pelt or anything. Never did bother them–they were pretty close with our people.

There’s a story I used to hear about the wolf, and so as I grew up, I had respect for the wolf, and when the wolf got brought back to Idaho, I went to Montana to greet them. They went down and tried to turn them loose, and then so many people objected, objected to the wolf turned loose in Idaho, that they chased them away. That wasn’t right to me, but then what can I say? That’s what happened.

They didn’t want the wolf back because. . .the stories that they heard about them killing the stock and all that, that’s what made them turn against the wolves. They’re still like that in Idaho. . .

I don’t know. . .they’re still going on. There’s nothing much I can do about it. All I can do is talk to my own people, still show respect for the wolf like my people did a long time ago. The connection still stands with my feelings. If I heard a wolf howl, I’d go investigate. I’m not afraid of them like [laughs], like some people are.

This man from Southern Idaho brought seven wolves up to our land in Lapwai, and he wanted a place to put them. . .a place for them to roam, to have wolves close by. . . I used to go up there to visit them, go right into the pen where they are. They come and put their paws on my hair and lick my face. That’s the way they greet you. I found that out; I wasn’t afraid of them. . .never got bit or anything.

That was my connection to the wolf. I still feel that way about the wolf. I’m not afraid of them, like some say they ought to be shot on sight. I’d sooner have a real eye connection with them; usually they look at you and then if they think you’re all right, they just walk away. I understand the wolf that way.

I never seen one shot yet, but I would probably object to that if I see it myself. . .

So this man from Idaho, from Southern Idaho, he brought these eight wolves up there, so I went up there. . .to greet the wolves at night. So I got my bell out and I start singing, and when I start singing, all the wolves start howling, every one of them, they howled as long as I was singing.

Axtell is not alone in feeling a special connection with the wolf. When wolves eventually were reintroduced to Idaho in 1995, the Nez Perce tribe took a leadership role in monitoring and reporting on individual wolves and packs.

But who or what is the wolf, beyond its representation in folklore and oral tradition? To better understand the wolf and our own reactions to it, let’s explore more of the history of its interactions with humans, its natural history, and its present biological and cultural status.

Continue to Wolves, Part III: The Historical Wolf

Print sources referenced in this section

James C. Burbank, “Great Beast God of the East,” from Vanishing Lobo: The Mexican Wolf in the Southwest (1990), rpt. in El Lobo: Readings on the Mexican Gray Wolf, ed. Tom Lynch. (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2005): 16-30.

Steve Pavlik, “Will Big Trotter Reclaim His Place? The Role of the Wolf in Navajo Tradition” (2000), in El Lobo: Readings on the Mexican Gray Wolf, ed. Tom Lynch. (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2005): 31-52.

Teresa Pijoan, White Wolf Woman: Native American Transformation Myths. (Little Rock: August House Publishers, Inc., 1992): 54-58.