Mt. Heyburn in central Idaho’s Sawtooth Mountain wilderness. Photo by Charles Knowles, and used under a Creative Commons license.

In 1980, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service published the Northern Rocky Mountain Wolf Recovery Plan, which provided a detailed plan for researching, reestablishing, and maintaining wolves in two portions of the wolves’ historic range: Yellowstone National Park and central Idaho. The FWS’s eventual goal was to return the wolf to a population of 30 breeding pairs for three successive years in three designated areas of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. Once that milestone had been reached, the report recommended turning management over to the states.

The 1980 report framed the need for federal action and oversight in the context of recent decades’ advances in civil rights protections and legislation:

Independent research on controversial subjects always necessitates stringent safeguards: in this case the very minimal act of separating the lead agency from local politics and prejudices.

To adequately grasp the importance of assigning the lead role in most tasks to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, one should compare the management of endangered species to civil rights legislation and administrative actions. In both cases the long tradition of states rights has been broken by federal legislation designed to protect minorities poorly treated by the majority. With regard to endangered species, there may be two minorities: the animals and the humans who advocate their preservation and restoration. Vigorous and lengthy federal civil rights action—by the judiciary, the Congress, and the executive—was required to force state compliance with national goals of the American people. Voluntary action by individual states was limited. The national will, as expressed in the Endangered Species Act, has occasionally forced state and local concerns to be subordinated to larger issues. . . .

The conclusion of this analysis is clear: there is an unmistakable mandate for federal action to implement a Recovery Plan that would otherwise languish under state inaction or biased performance. Again, it bears repeating: the objectively predictable outcome of allowing state assumption of major recovery tasks will be the partial if not complete failure of the plan to accomplish its objective.” (61-62)

From our perspective in the second decade of the twenty-first century, such an application of civil rights legislation designed to protect people of color, and African-Americans in particular, may strike us as a remote and theoretical application of legal precedent, but recall that in 1980, the Civil Rights Act outlawing discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin was still relatively new legislation—it was but 16 years old. People still bore the physical and emotional scars of the civil rights movement. Those who bothered to read the report likely had an emotional or even visceral reaction to the report’s author’s invocation of civil rights law in the context of wolf protection and recovery. It was, in short, a new call to arms for progressives who might have been casting about for their next cause.

The cover of the 1987 recovery plan

In 1987, the FWS raised its investment in wolves significantly when it updated its 1980 Northern Rocky Mountain Wolf Recovery Plan. The plan called for the establishment of ten breeding pairs, and total of at least 100 wolves, in three core recovery areas—including central Idaho. The report estimated that in 1987, Idaho supported a population of no more than 15 wolves, none of them paired.

Little Redfish Lake in central Idaho’s Sawtooth Mountains. Photo by Charles Knowles, and used under a Creative Commons license.

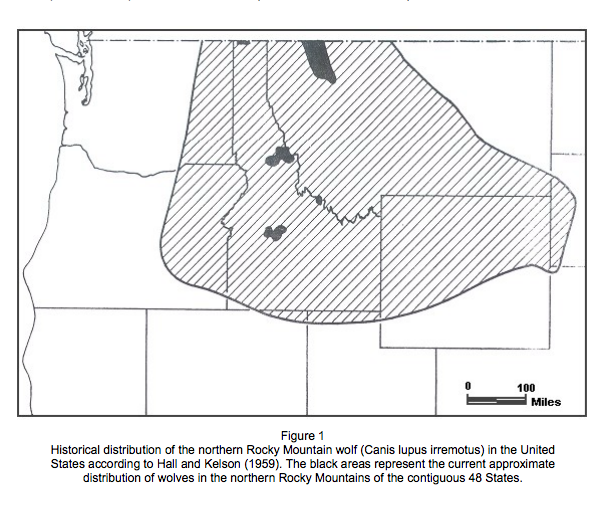

A map from the 1987 plan

The 1987 plan drew on field observations and research on wolf prey and habitat. In determining the best place to relocate breeding pairs of wolves, the report’s authors maintained that

Ungulates comprise the major component of wolf diet throughout central Idaho. Elk, mule deer, white-tailed deer, and moose were available, are the primary prey species. Columbian ground squirrels, snowshoe hare, and grouse are available to wolves in central Idaho as an alternate prey source. Beaver, an important alternate prey source for wolves in some areas of North America, are scarce over most of central Idaho.

Idaho National Forests in the north-central (Clearwater, Nez Perce, Bitterroot), and west-central (Payette, Boise) part of the Central Idaho Area support more natural prey-biomass per wolf than do other forests (challis, Sawtooth, Salmon) at this time, and thus would probably support more wolves with fewer conflicts. Also, fewer livestock are grazed on north and west-central forests within or near the Central Idaho Area resulting in less potential for livestock conflicts in key areas.

The plan listed three objectives:

Primary Objective: To remove the Northern Rocky Mountain wolf from the endangered and threatened species list by securing and maintaining a minimum of ten breeding pairs in each of the three recovery areas for a minimum of three successive years.

Secondary Objective: To reclassify the Northern Rocky Mountain wolf to threatened status over its entire range by securing and maintaining a minimum of ten breeding pairs in each of two recovery areas for a minimum of three successive years.

Tertiary Objective: To reclassify the Northern Rocky Mountain wolf to threatened status in an individual recovery area by securing and maintaining a minimum of ten breeding pairs in the recovery area for a minimum of three successive years. Consideration will also be given to reclassifying such a population to threatened under similarity of appearance after the tertiary objective for the population has been achieved and verified, special regulations are established, and a State management plan is in place for that population.

The conclusions drawn by these reports seem straightforward: Ethically and legally, it was the federal government’s responsibility to ensure wolves received the protection and assistance they needed to thrive, and Idaho was an ideal place for the reintroduction of wolves.

Idahoans, however, were not persuaded wolf reintroduction was the best idea.

Continue to Wolves, Part V: Resistance and negotiation (Coming soon!)